Introduction

After the invention of photography, many have questioned the meaning of perceptual painting. Photography seems capable of sufficiently capturing reality. But can perceptual painting provide something “real” aside from what the camera can? How has the visual language of photography in turn influenced perceptual painting?

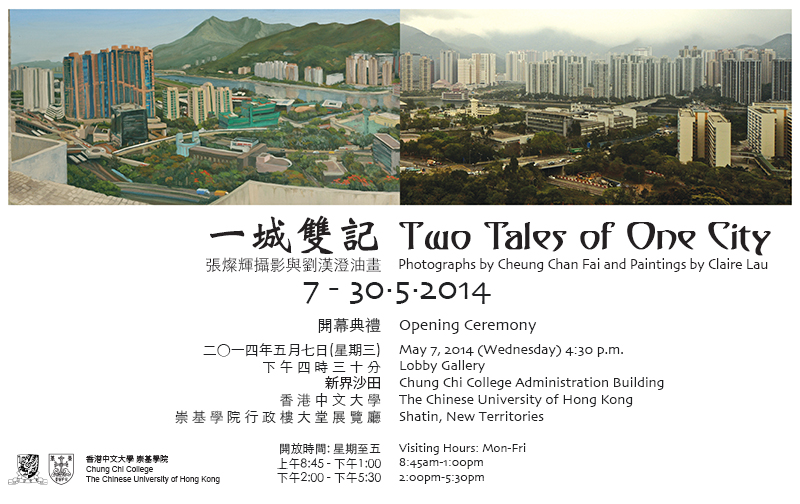

Prof. Cheung Chan Fai and Claire Lau have both been fascinated by the experience of the landscape for a long time. Both search for unusual ways to observe and understand the space which we occupy. Gazing upward while inside a building, looking down to the city or fields from a plane, Prof. Cheung's photographs capture curious perspectives of the land. Claire climbs atop skyscrapers or rooftops and investigates the systems and structures of the city through painting large landscapes on site. Having both lived abroad and regularly travelled, the two artists find Hong Kong's juxtapositions of heterogeneous elements very unique: skyscrapers leaning against wild forested mountains, old village houses beside modern high rises, and highways winding between buildings and hills, linking everything. Realizing this shared interest, the two embarked on a project to describe the same locations through their respective mediums.

Claire’s paintings respond to elements that speak to her at each location, be it the air quality, the dynamic infrastructure, or the lush greenery unfolding by the hillside. Standing at the edge of rooftops, she observes the spaces around her, from her feet to the horizon and as far as her head can turn. While combing these different angles onto a single flat surface, Claire rebuilds the landscape with curved perspectives that often remind one of wide-angle or fisheye lenses. But these compositions are actually drawn purely form from experience, and are a result of turning the head, hence shifting the distance between the artist and the subject. However, it is true that this idea of viewing space from a single stand point and turning the head has only been widely explored by artists after the advent of the camera. Previously, artists predominantly either used stand-still linear perspectives established in the Renaissance using straight focal lines, or, when painting panoramas, used shifting perspectives that also implied shifting the position of the viewer (this is also the case in Chinese ink landscapes). However, when photographers began to create panoramas in the 19th Century, they would stand in one spot and rotate their cameras, resulting in a combination of images that create curves, contradicting the mainstream Renaissance theories of straight line perspectives. By the 1970s and 80s, some artists began to explore this way of viewing space, but these have not gained much attention until recently when perceptual landscapes and interior paintings have resurged into the contemporary art scene.

While working on this project, Claire and Prof. Cheung have made some interesting discoveries for themselves. Looking at Chan Fai’s photographs, Claire realized that her brain inadvertently rationalises the expanses around her and makes transitions between viewpoints sometimes too smooth and logical. This “normalises” the landscape for the viewer and can reduce the impact of the scene. However, the brain is still flexible in its creation/depiction of space. It chooses its emphasis, accentuates it and fits other elements together to support the composition. While wide-angle and fisheye lenses can produce extremely dynamic images, the lenses are usually limited to 180º and are restricted to their mapping function (manner of distortion). That is why at some sites, Prof. Cheung had to change the elevation of the viewpoint to compensate for the distortion of the lenses. Another issue was that at one site (Ha Wo Che Village), Claire observed the scene through a netted fence, which the camera could not remove like the brain can. This forced the camera to capture the scene from a completely different perspective. The process of preparing for the exhibition has enabled increased cross-understanding between the artists, but has also revealed to them the strengths and limitations of their own mediums. This will encourage them to further pursue their mediums to their full and unique potentials.

This project aims to create a direct dialogue between photography and painting, providing a platform where these two nowadays inextricably linked mediums can be analysed side by side. We do not wish the viewer to ask how much the paintings look like photographs, but whether they can bring dimensions beyond what can be seen in a photograph. We do not wish viewer to only ask whether the photographs are beautiful or not, but to what extent they represent our experience of reality.

Claire Lau, May 2014

Prof. Cheung Chan Fai and Claire Lau have both been fascinated by the experience of the landscape for a long time. Both search for unusual ways to observe and understand the space which we occupy. Gazing upward while inside a building, looking down to the city or fields from a plane, Prof. Cheung's photographs capture curious perspectives of the land. Claire climbs atop skyscrapers or rooftops and investigates the systems and structures of the city through painting large landscapes on site. Having both lived abroad and regularly travelled, the two artists find Hong Kong's juxtapositions of heterogeneous elements very unique: skyscrapers leaning against wild forested mountains, old village houses beside modern high rises, and highways winding between buildings and hills, linking everything. Realizing this shared interest, the two embarked on a project to describe the same locations through their respective mediums.

Claire’s paintings respond to elements that speak to her at each location, be it the air quality, the dynamic infrastructure, or the lush greenery unfolding by the hillside. Standing at the edge of rooftops, she observes the spaces around her, from her feet to the horizon and as far as her head can turn. While combing these different angles onto a single flat surface, Claire rebuilds the landscape with curved perspectives that often remind one of wide-angle or fisheye lenses. But these compositions are actually drawn purely form from experience, and are a result of turning the head, hence shifting the distance between the artist and the subject. However, it is true that this idea of viewing space from a single stand point and turning the head has only been widely explored by artists after the advent of the camera. Previously, artists predominantly either used stand-still linear perspectives established in the Renaissance using straight focal lines, or, when painting panoramas, used shifting perspectives that also implied shifting the position of the viewer (this is also the case in Chinese ink landscapes). However, when photographers began to create panoramas in the 19th Century, they would stand in one spot and rotate their cameras, resulting in a combination of images that create curves, contradicting the mainstream Renaissance theories of straight line perspectives. By the 1970s and 80s, some artists began to explore this way of viewing space, but these have not gained much attention until recently when perceptual landscapes and interior paintings have resurged into the contemporary art scene.

While working on this project, Claire and Prof. Cheung have made some interesting discoveries for themselves. Looking at Chan Fai’s photographs, Claire realized that her brain inadvertently rationalises the expanses around her and makes transitions between viewpoints sometimes too smooth and logical. This “normalises” the landscape for the viewer and can reduce the impact of the scene. However, the brain is still flexible in its creation/depiction of space. It chooses its emphasis, accentuates it and fits other elements together to support the composition. While wide-angle and fisheye lenses can produce extremely dynamic images, the lenses are usually limited to 180º and are restricted to their mapping function (manner of distortion). That is why at some sites, Prof. Cheung had to change the elevation of the viewpoint to compensate for the distortion of the lenses. Another issue was that at one site (Ha Wo Che Village), Claire observed the scene through a netted fence, which the camera could not remove like the brain can. This forced the camera to capture the scene from a completely different perspective. The process of preparing for the exhibition has enabled increased cross-understanding between the artists, but has also revealed to them the strengths and limitations of their own mediums. This will encourage them to further pursue their mediums to their full and unique potentials.

This project aims to create a direct dialogue between photography and painting, providing a platform where these two nowadays inextricably linked mediums can be analysed side by side. We do not wish the viewer to ask how much the paintings look like photographs, but whether they can bring dimensions beyond what can be seen in a photograph. We do not wish viewer to only ask whether the photographs are beautiful or not, but to what extent they represent our experience of reality.

Claire Lau, May 2014

展覽序言

自從人類發明攝影之後,具象繪畫不斷被質疑,攝影好像最能捕捉真實。具象繪畫能夠帶出鏡頭以外的「真」嗎?攝影的視覺語言又有影響到具象繪畫嗎?

今次展出作品的張燦輝教授和劉漢澄小姐兩位藝術家,長久以來一直熱愛捕捉風景的「真」,用不尋常的角度來觀察和分析我們身處的空間。張教授的攝影作品中有不少從大型建築物內抬頭望天花,有些卻從飛機上往下眺望城市或田園。漢澄則爬上高樓大廈的頂樓或天台,當場用寫生方式探究市城的空間結構。由於兩者都曾經在外國生活,現在又經常外遊,他們都察覺到香港景色特別之處在於異質元素的並列:山野與市鎮、小村落與高樓大廈;而公路在山丘與樓房之間穿插,將一切連結起來。眼見大家喜歡的主題相近,於是決定一起籌辦一個攝影與繪畫的雙人展,用各自的藝術手段捕捉同樣的風景。

漢澄的每一幅作品都是她對每一個景觀作出的回應。引起她注目的有空氣質素、城市架構、花木繁茂的山坡等。當她在天台欄杆邊觀察四周的環境時,從遠眺到腳下、由左至右,用畫筆把包圍著她的空間壓縮在一個平面上。有些人會用「魚眼鏡」形容這種視覺效果;但其實這些構圖出於畫家頭和眼的轉動,以致主題和畫家之間的距離轉變。然而,這種視覺手法的確是在攝影發明之後才得到一些畫家認真探索。自從文藝復興時代開始西方繪畫採用直缐的線透視法,意味著觀者站在一點視察景象,而畫廣角景色時就跟中國國畫一樣用散點透視法,即是觀者從多個觀點觀看風景,造出邊走邊看的效果。到攝影開始普及時,攝影師們多數站在一點,然後轉移鏡頭,拼造出的圖片不是文藝復興式的直線透視,而是具曲缐的透視效果。到二十世紀70至80年代,有些畫家開始探索這種構圖,但直至近期具象戶外和室內風景畫復興,才在當代藝術題材中看到多些曲線透視的運用。

張教授和漢澄在籌備展覽期間對繪畫與攝影都有新發現。看見張教授的攝影後,漢澄意識到自己的腦袋裏原來不自覺地把四周空間合理化,將不同的角度融合得太自然順暢,造出的畫面顯得較為平常,令觀眾誤以為這只是普通的寫實,感受不到畫面帶來的衝擊。但與相機對比,人的腦袋亦是較為靈活的,可選擇強調某些元素,其他元素則只有襯托作用。雖然用廣角鏡和魚眼鏡可拍出充滿力量的照片,多數鏡頭最大只有180度,而受到特定的桶狀變形局限。因此張教授在拍攝某些景點時需要改變觀景的高度才能順應桶狀變形的限制。另外,在下禾輋村時,漢澄是透過鐵絲網觀察景色,但相機無法像腦袋一樣抽除鐵絲網,因此張教授最後要從一個完全不同的角度拍攝該景。總的來說,這合作經驗不但使兩位加深了對彼此藝術媒介的認識,也令他們對各自藝術手段的潛能與局限有更深入的了解。希望這些得益會成為推進以後作品的動力。

這次展覽是攝影與油畫的一埸直接對話,更是兩個現時關係密切的藝術媒介之間的對照和分析。我們並不希望觀眾問畫作畫得有多像相片,而是問究竟它們能否帶出攝影裏找不到的元素。我們不希望觀眾只是問相片是否美麗,而問它們在什麼程度上能表達我們對真實的體驗。

劉漢澄, 2014年5月

今次展出作品的張燦輝教授和劉漢澄小姐兩位藝術家,長久以來一直熱愛捕捉風景的「真」,用不尋常的角度來觀察和分析我們身處的空間。張教授的攝影作品中有不少從大型建築物內抬頭望天花,有些卻從飛機上往下眺望城市或田園。漢澄則爬上高樓大廈的頂樓或天台,當場用寫生方式探究市城的空間結構。由於兩者都曾經在外國生活,現在又經常外遊,他們都察覺到香港景色特別之處在於異質元素的並列:山野與市鎮、小村落與高樓大廈;而公路在山丘與樓房之間穿插,將一切連結起來。眼見大家喜歡的主題相近,於是決定一起籌辦一個攝影與繪畫的雙人展,用各自的藝術手段捕捉同樣的風景。

漢澄的每一幅作品都是她對每一個景觀作出的回應。引起她注目的有空氣質素、城市架構、花木繁茂的山坡等。當她在天台欄杆邊觀察四周的環境時,從遠眺到腳下、由左至右,用畫筆把包圍著她的空間壓縮在一個平面上。有些人會用「魚眼鏡」形容這種視覺效果;但其實這些構圖出於畫家頭和眼的轉動,以致主題和畫家之間的距離轉變。然而,這種視覺手法的確是在攝影發明之後才得到一些畫家認真探索。自從文藝復興時代開始西方繪畫採用直缐的線透視法,意味著觀者站在一點視察景象,而畫廣角景色時就跟中國國畫一樣用散點透視法,即是觀者從多個觀點觀看風景,造出邊走邊看的效果。到攝影開始普及時,攝影師們多數站在一點,然後轉移鏡頭,拼造出的圖片不是文藝復興式的直線透視,而是具曲缐的透視效果。到二十世紀70至80年代,有些畫家開始探索這種構圖,但直至近期具象戶外和室內風景畫復興,才在當代藝術題材中看到多些曲線透視的運用。

張教授和漢澄在籌備展覽期間對繪畫與攝影都有新發現。看見張教授的攝影後,漢澄意識到自己的腦袋裏原來不自覺地把四周空間合理化,將不同的角度融合得太自然順暢,造出的畫面顯得較為平常,令觀眾誤以為這只是普通的寫實,感受不到畫面帶來的衝擊。但與相機對比,人的腦袋亦是較為靈活的,可選擇強調某些元素,其他元素則只有襯托作用。雖然用廣角鏡和魚眼鏡可拍出充滿力量的照片,多數鏡頭最大只有180度,而受到特定的桶狀變形局限。因此張教授在拍攝某些景點時需要改變觀景的高度才能順應桶狀變形的限制。另外,在下禾輋村時,漢澄是透過鐵絲網觀察景色,但相機無法像腦袋一樣抽除鐵絲網,因此張教授最後要從一個完全不同的角度拍攝該景。總的來說,這合作經驗不但使兩位加深了對彼此藝術媒介的認識,也令他們對各自藝術手段的潛能與局限有更深入的了解。希望這些得益會成為推進以後作品的動力。

這次展覽是攝影與油畫的一埸直接對話,更是兩個現時關係密切的藝術媒介之間的對照和分析。我們並不希望觀眾問畫作畫得有多像相片,而是問究竟它們能否帶出攝影裏找不到的元素。我們不希望觀眾只是問相片是否美麗,而問它們在什麼程度上能表達我們對真實的體驗。

劉漢澄, 2014年5月