看與見 – 看劉漢澄近作感想

戴海鷹

繪畫的真實:「看」還是「見」?

“To be or not to be” 這句莎士比亞名言,在哈姆萊雷特悲劇第三幕,王子上場時的第一句話;因王子經鬼魂指示,策劃復仇,裝瘋佯狂,反常、挑衅、顛覆…實在或虛無成為問題;再見女友之前,不期然而疑問真實!其實,早在漢朝,武帝寵妃李夫人,年輕早逝。武帝眷戀至極,經術士裝置,在燈光下、帷幕間,漢武帝再見李夫人。因不許接近,武帝情急,悲感而作詩,第一句就是「是耶?非耶?」亦是不期然而疑問起真實。漢武帝李夫人歌:「是耶?非耶?立予望之,偏何姍姍其來遲!」1

如何能洞見真實呢?人能夠「明足以察秋毫之末」,卻又可能「不見輿薪」,視而不見!2

1906年,畢加索在畫室面對 Gertrude Stein 作肖像。畫到第九十次時,畢加索說:「我看着您卻見不到您了。」(“Je ne vous vois plus quand je vous regarde.”)隨即塗掉整個臉孔。暑期後歸來,卻在沒有對照模特兒的情況下完成畫像,而感覺適意。畢加索以見而不視的方式完成了著名的 G. Stein 畫像。3

畢加索的方式,A. Giacometti 不以為然。4 畫家堅持要面對對象,不停去看,手與眼活動在時間當中,在逐分逐秒消逝的時間中活動;活動的痕跡留落在畫面,畫面留存了追求造型的過程的痕跡。於是流逝了時間的畫面上,保存時間正在消逝的真實影跡。A.Giacometti 的堅持,無疑是追隨塞尚的追求而遠離超現實主義潮流。1937年以廚櫃上的一個蘋果又重新開始對著真實探索,簡單的對象,確實的空間,確定的觀察點,反覆觀測,反覆在畫面描繪,直至影像的呈現適意。

自然的真實:持久的探索還是剎那的衝動?

塞尚的疑問是從時間開始,「世上消逝的一分鐘,畫家正在真實中!」「這是我們所見的一切,分散、消逝。大自然總是這樣,從來沒有片刻暫留,就這樣顯示給我們。我們的藝術應以種種元素給出時間的蕩漾,呈現一切都在變化的狀態,應樣我們體會永恆。」在塞尚眼中,「自然遠比表象深刻」,故必需「漫長工作,沉思,研究,種種痛苦和種種快樂…」在松蔭下、工作了兩個月的一幅風景畫,一日復一日緩慢地約制每一對象、每一色調,不知不覺地成全了和諧。塞尚自覺藝術不是低於自然,「藝術是一種平行於自然的和諧」。直到1904 年塞尙作總括,指出「應首先在幾何型體上做研究:錐形、立方形、圓球形,當懂得把這些東西運用到形態上和平面上,我們便懂得繪畫了。」5 1906年塞尚逝世,他終生的努力的成果,「讓我們體會永恆」,成為二十世紀藝術的指南。

與塞尚同時代,但與塞尚性格不同的梵高,卻以短促的一生(1853-1890)急速、熱情、勤奮、焦慮,投身繪畫生涯只有短短的十年,同樣成為二十世紀藝術的楷模。我們見到「遲速異分」、「殊途同歸」,藝術領域的現象正如生活現象。

超越表面:模仿、機械複製與真實

我們再從古今變異去看藝術工作。十四世紀意大利畫家 Cennino Cennini 於1396年(或說1437年)寫成《藝術之書》(Il libro dell’arte),書中以喬托(Giotto)畫派三代傳人的學藝經驗(Cennino Cennini 從師十二年,師公跟從喬托學藝二十四年),說明須長期隨師學習,才能具備靈巧的手和想像力,去模仿自然,去創作繪畫。時代一直在改變,至十八世紀法國畫家Chardin,仍承受長期學藝的方式。一次與哲學家、批評家狄德羅(Diderot)的對話(見《1765年的沙龍》),畫家請批評家評畫時筆下留情,懇請體會長期研習繪畫的艱難…。但狄德羅不寬容平庸的「自然的模仿」,而指向「自然的真實」的要求。到十九世紀,空前激進的工業步伐,使平庸的模仿手藝更不合時宜。1835年畫家 Daguerre 實現了「以光為畫筆」的夢想,第一幅攝影照片問世。1839年正式公認攝影術的發明6,迅速捕捉如實影像,迅速複製。攝影工藝日趨精確,更快更簡便,快速在全世界普及、流行。今日,我們日常生活已成離不開攝影術的現代生活。

在現代生活中,依然存在對「真實」的疑問。攝影流行的年代,塞尚、梵高,以至馬蒂斯、畢加索,直至Giacometti、Balthus…等等,依舊以繪畫去尋求「自然的真實」。馬蒂斯以童真的眼光重新去看世界,Giacometti 面對同一模特兒而每日所見不同…。

真實:從自然到人間

我們在攝影錄像的機械技術主宰影像的時代,來看劉漢澄的一組繪畫:15幅以香港榕樹為素材,12幅以香港實景作構圖。初看畫面任由榕根縱橫闖蕩,盤根蒼老,逶曲離奇。難免疑問:如何會從劉漢澄的少女眼光去演繹呢?隨即想起梵高第一幅油畫《林間白衣少女》(Jeune fille en blanc dans un bois, 1882),就是以一排三棵老樹作構圖,杈枒樹根作前景,中景白衣少女站在第二棵樹根上,扶倚大樹;前景老根出奇的超前,使少女顯得細小而遠離,可望而不可及,很有求之不能又揮之不去,令人惆悵。少女和樹根原應鉏鋙難合,何至共處樹林蒼莽中?在西方就說是「憂鬱」(mélancolie),看成人間自古潛藏的情緒。另一幅梵高最晚期作品《樹幹與草地花開》(Troncs d’arbres avec pré fleuri, 1890) ,前景也是老樹粗幹,以粗老、痙攣、急促的筆觸冒起,至地面草卉,再至中景開花的草地,漸去漸遠逐漸融和,直至更遠一切平和…。是梵高流露的「鄉愁」?畫面明麗的鵝黃嫩綠色調,黑綫夾帶着藍和紅,由粗魯而至細蜜,編織成充滿張力的節奏,己足見純粹的畫味,足以娛目欣賞了。卻要分明是皺褶的老樹幹,點明花開時分,發生在極近而至極遠的大地上…。大地無限遼遠,意味着異鄕人的故鄉渺漠,能不是鄉愁!梵高借老樹根幹襯托風景,表現出潛藏在人間的「憂鬱」與「鄉愁」,就是我們要討論的揭示「真實」。

“To be or not to be” 這句莎士比亞名言,在哈姆萊雷特悲劇第三幕,王子上場時的第一句話;因王子經鬼魂指示,策劃復仇,裝瘋佯狂,反常、挑衅、顛覆…實在或虛無成為問題;再見女友之前,不期然而疑問真實!其實,早在漢朝,武帝寵妃李夫人,年輕早逝。武帝眷戀至極,經術士裝置,在燈光下、帷幕間,漢武帝再見李夫人。因不許接近,武帝情急,悲感而作詩,第一句就是「是耶?非耶?」亦是不期然而疑問起真實。漢武帝李夫人歌:「是耶?非耶?立予望之,偏何姍姍其來遲!」1

如何能洞見真實呢?人能夠「明足以察秋毫之末」,卻又可能「不見輿薪」,視而不見!2

1906年,畢加索在畫室面對 Gertrude Stein 作肖像。畫到第九十次時,畢加索說:「我看着您卻見不到您了。」(“Je ne vous vois plus quand je vous regarde.”)隨即塗掉整個臉孔。暑期後歸來,卻在沒有對照模特兒的情況下完成畫像,而感覺適意。畢加索以見而不視的方式完成了著名的 G. Stein 畫像。3

畢加索的方式,A. Giacometti 不以為然。4 畫家堅持要面對對象,不停去看,手與眼活動在時間當中,在逐分逐秒消逝的時間中活動;活動的痕跡留落在畫面,畫面留存了追求造型的過程的痕跡。於是流逝了時間的畫面上,保存時間正在消逝的真實影跡。A.Giacometti 的堅持,無疑是追隨塞尚的追求而遠離超現實主義潮流。1937年以廚櫃上的一個蘋果又重新開始對著真實探索,簡單的對象,確實的空間,確定的觀察點,反覆觀測,反覆在畫面描繪,直至影像的呈現適意。

自然的真實:持久的探索還是剎那的衝動?

塞尚的疑問是從時間開始,「世上消逝的一分鐘,畫家正在真實中!」「這是我們所見的一切,分散、消逝。大自然總是這樣,從來沒有片刻暫留,就這樣顯示給我們。我們的藝術應以種種元素給出時間的蕩漾,呈現一切都在變化的狀態,應樣我們體會永恆。」在塞尚眼中,「自然遠比表象深刻」,故必需「漫長工作,沉思,研究,種種痛苦和種種快樂…」在松蔭下、工作了兩個月的一幅風景畫,一日復一日緩慢地約制每一對象、每一色調,不知不覺地成全了和諧。塞尚自覺藝術不是低於自然,「藝術是一種平行於自然的和諧」。直到1904 年塞尙作總括,指出「應首先在幾何型體上做研究:錐形、立方形、圓球形,當懂得把這些東西運用到形態上和平面上,我們便懂得繪畫了。」5 1906年塞尚逝世,他終生的努力的成果,「讓我們體會永恆」,成為二十世紀藝術的指南。

與塞尚同時代,但與塞尚性格不同的梵高,卻以短促的一生(1853-1890)急速、熱情、勤奮、焦慮,投身繪畫生涯只有短短的十年,同樣成為二十世紀藝術的楷模。我們見到「遲速異分」、「殊途同歸」,藝術領域的現象正如生活現象。

超越表面:模仿、機械複製與真實

我們再從古今變異去看藝術工作。十四世紀意大利畫家 Cennino Cennini 於1396年(或說1437年)寫成《藝術之書》(Il libro dell’arte),書中以喬托(Giotto)畫派三代傳人的學藝經驗(Cennino Cennini 從師十二年,師公跟從喬托學藝二十四年),說明須長期隨師學習,才能具備靈巧的手和想像力,去模仿自然,去創作繪畫。時代一直在改變,至十八世紀法國畫家Chardin,仍承受長期學藝的方式。一次與哲學家、批評家狄德羅(Diderot)的對話(見《1765年的沙龍》),畫家請批評家評畫時筆下留情,懇請體會長期研習繪畫的艱難…。但狄德羅不寬容平庸的「自然的模仿」,而指向「自然的真實」的要求。到十九世紀,空前激進的工業步伐,使平庸的模仿手藝更不合時宜。1835年畫家 Daguerre 實現了「以光為畫筆」的夢想,第一幅攝影照片問世。1839年正式公認攝影術的發明6,迅速捕捉如實影像,迅速複製。攝影工藝日趨精確,更快更簡便,快速在全世界普及、流行。今日,我們日常生活已成離不開攝影術的現代生活。

在現代生活中,依然存在對「真實」的疑問。攝影流行的年代,塞尚、梵高,以至馬蒂斯、畢加索,直至Giacometti、Balthus…等等,依舊以繪畫去尋求「自然的真實」。馬蒂斯以童真的眼光重新去看世界,Giacometti 面對同一模特兒而每日所見不同…。

真實:從自然到人間

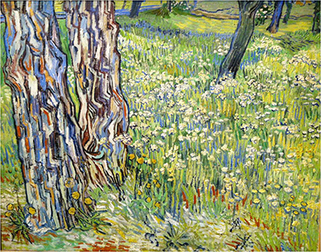

我們在攝影錄像的機械技術主宰影像的時代,來看劉漢澄的一組繪畫:15幅以香港榕樹為素材,12幅以香港實景作構圖。初看畫面任由榕根縱橫闖蕩,盤根蒼老,逶曲離奇。難免疑問:如何會從劉漢澄的少女眼光去演繹呢?隨即想起梵高第一幅油畫《林間白衣少女》(Jeune fille en blanc dans un bois, 1882),就是以一排三棵老樹作構圖,杈枒樹根作前景,中景白衣少女站在第二棵樹根上,扶倚大樹;前景老根出奇的超前,使少女顯得細小而遠離,可望而不可及,很有求之不能又揮之不去,令人惆悵。少女和樹根原應鉏鋙難合,何至共處樹林蒼莽中?在西方就說是「憂鬱」(mélancolie),看成人間自古潛藏的情緒。另一幅梵高最晚期作品《樹幹與草地花開》(Troncs d’arbres avec pré fleuri, 1890) ,前景也是老樹粗幹,以粗老、痙攣、急促的筆觸冒起,至地面草卉,再至中景開花的草地,漸去漸遠逐漸融和,直至更遠一切平和…。是梵高流露的「鄉愁」?畫面明麗的鵝黃嫩綠色調,黑綫夾帶着藍和紅,由粗魯而至細蜜,編織成充滿張力的節奏,己足見純粹的畫味,足以娛目欣賞了。卻要分明是皺褶的老樹幹,點明花開時分,發生在極近而至極遠的大地上…。大地無限遼遠,意味着異鄕人的故鄉渺漠,能不是鄉愁!梵高借老樹根幹襯托風景,表現出潛藏在人間的「憂鬱」與「鄉愁」,就是我們要討論的揭示「真實」。

劉漢澄的繪畫:自然的生命

回到劉漢澄作品的榕樹系列,繪畫意圖也明顯不在榕樹的植物類型。試看《根(三)》:以一道白籬橫過,巧妙地攔開林木,只見一棵榕樹的老根,只有根在大地延伸;我們專注樹根,地上交替著光與暗的斑駁,生命就是這樣不動聲色地蔓延。對照樹幹光斑的暖色,陰影裡樹根的灰綠,顯得特別深沉,毫不炫耀,這是頑強生命力的寫照!再看《破土而出》,也是讓人注視老根。但這裡光暗對比已不再重要,卻見凸出紅磚白石的包圍。老根的活力仍是主題:盤根虯結,根石糾纏。在畫中,根和石都同樣用粗黑線條勾勒,突出嚴峻冷冽的紅磚白石規範的力量,而畫家又寄望暗綠的根和草,作為生命,作為動力,在火紅的色調中,突破就是勝利!縱觀組畫,借榕根的《交織》、《抓緊》、《伸展》… 直至《擁抱》,不難令觀者聯系聽見貝多芬交響曲,聽至《大合唱》時的激情!

城市景色:真實的探究

我們來看第二部分香港風景:從《天朗氣清》開始,接著《沙田(一)》-濕潤的陵坡上仍由木屋和老宅襯托隆起的山陵。《沙田(二)》-沙田低谷的舊屋,對照新建築高樓住宅。《城門上河圖》-城門河沿岸,住宅高樓林立。至到《新與舊(中環》,其中間隔《葵涌(一)》、《葵涌(二)》等等,都是地標明確的香港民居區。不見香港的旅遊標誌太平山,不見金融商業揚威的摩天大廈群,不見全城名牌並列的商場繁華、名車如流的街道氣勢…。畫家的眼光顯然無意照顧旅遊來客的獵奇目標。畫家的眼光是實在生活在香港所見的香港實景,香港人看香港生活就應平實無奇。現時,即使外鄉人來看香港生活,也應同樣感覺平實無奇。今天,全球一體化的消費社會、一體化的消費動力、一體化的生活方式,到處同樣無從講究別樣、另類。但是,平實無奇的環境風景表現在繪畫中,我們仍然要求十八世紀狄德羅的態度──不寬容平庸的「自然的模仿」。 我們看香港組畫最後一幅:仰望鬱綠山陵頂上一排水泥大廈,由天空襯出高聳,卻有說不清的孤立、落寞。令人還想回看沙田、葵涌、火炭的生活,活動、喧鬧。從仰望回至俯瞰,落寞至喧鬧的面面觀,想是畫家正在追求的「自然的真實」罷。

看漢澄繪畫,始自漢澄携孩年代。在巴黎每次見面,都看新作,直至隨父母遷返香港。多年之後再看漢澄的作品,是一幅人物畫,敏感敏銳的表現力,至今猶存記憶。後來漢澄赴美國留學主修美術,隨學校課程再來巴黎實習,在巴黎又看到漢澄留學期間繪畫作業。甲午新年,收到漢澄近作照片。這回不由得不為漢澄作品寫下一段看畫感受。不避文字外行,不嫌貽笑方家。

2014新春

1《漢書·外戚傳》

2《孟子·梁惠王》

3 Gertrude Stein, Autobiographie, 1934; Picasso, 1938.

4 James Lord, Un portrait de Giacometti, 1965 ; Giacometti biographie, 1983.

5 Conversations avec Cézanne, 1978, Macula.

6 Le daguerréotype français. Un objet photographique. Paris: Musée d’Orsay, 2003.

-----

戴海鷹是著名華裔旅法畫家,1970年起在巴黎工作生活,過去四十年在世界各地的美術館和畫廊廣泛展出,展地包括法國丶 瑞士 丶 丹麥 丶比利時 丶 台灣 丶澳門丶香港丶 美國等。

回到劉漢澄作品的榕樹系列,繪畫意圖也明顯不在榕樹的植物類型。試看《根(三)》:以一道白籬橫過,巧妙地攔開林木,只見一棵榕樹的老根,只有根在大地延伸;我們專注樹根,地上交替著光與暗的斑駁,生命就是這樣不動聲色地蔓延。對照樹幹光斑的暖色,陰影裡樹根的灰綠,顯得特別深沉,毫不炫耀,這是頑強生命力的寫照!再看《破土而出》,也是讓人注視老根。但這裡光暗對比已不再重要,卻見凸出紅磚白石的包圍。老根的活力仍是主題:盤根虯結,根石糾纏。在畫中,根和石都同樣用粗黑線條勾勒,突出嚴峻冷冽的紅磚白石規範的力量,而畫家又寄望暗綠的根和草,作為生命,作為動力,在火紅的色調中,突破就是勝利!縱觀組畫,借榕根的《交織》、《抓緊》、《伸展》… 直至《擁抱》,不難令觀者聯系聽見貝多芬交響曲,聽至《大合唱》時的激情!

城市景色:真實的探究

我們來看第二部分香港風景:從《天朗氣清》開始,接著《沙田(一)》-濕潤的陵坡上仍由木屋和老宅襯托隆起的山陵。《沙田(二)》-沙田低谷的舊屋,對照新建築高樓住宅。《城門上河圖》-城門河沿岸,住宅高樓林立。至到《新與舊(中環》,其中間隔《葵涌(一)》、《葵涌(二)》等等,都是地標明確的香港民居區。不見香港的旅遊標誌太平山,不見金融商業揚威的摩天大廈群,不見全城名牌並列的商場繁華、名車如流的街道氣勢…。畫家的眼光顯然無意照顧旅遊來客的獵奇目標。畫家的眼光是實在生活在香港所見的香港實景,香港人看香港生活就應平實無奇。現時,即使外鄉人來看香港生活,也應同樣感覺平實無奇。今天,全球一體化的消費社會、一體化的消費動力、一體化的生活方式,到處同樣無從講究別樣、另類。但是,平實無奇的環境風景表現在繪畫中,我們仍然要求十八世紀狄德羅的態度──不寬容平庸的「自然的模仿」。 我們看香港組畫最後一幅:仰望鬱綠山陵頂上一排水泥大廈,由天空襯出高聳,卻有說不清的孤立、落寞。令人還想回看沙田、葵涌、火炭的生活,活動、喧鬧。從仰望回至俯瞰,落寞至喧鬧的面面觀,想是畫家正在追求的「自然的真實」罷。

看漢澄繪畫,始自漢澄携孩年代。在巴黎每次見面,都看新作,直至隨父母遷返香港。多年之後再看漢澄的作品,是一幅人物畫,敏感敏銳的表現力,至今猶存記憶。後來漢澄赴美國留學主修美術,隨學校課程再來巴黎實習,在巴黎又看到漢澄留學期間繪畫作業。甲午新年,收到漢澄近作照片。這回不由得不為漢澄作品寫下一段看畫感受。不避文字外行,不嫌貽笑方家。

2014新春

1《漢書·外戚傳》

2《孟子·梁惠王》

3 Gertrude Stein, Autobiographie, 1934; Picasso, 1938.

4 James Lord, Un portrait de Giacometti, 1965 ; Giacometti biographie, 1983.

5 Conversations avec Cézanne, 1978, Macula.

6 Le daguerréotype français. Un objet photographique. Paris: Musée d’Orsay, 2003.

-----

戴海鷹是著名華裔旅法畫家,1970年起在巴黎工作生活,過去四十年在世界各地的美術館和畫廊廣泛展出,展地包括法國丶 瑞士 丶 丹麥 丶比利時 丶 台灣 丶澳門丶香港丶 美國等。

Gaze and Vision: Thoughts on Claire Lau’s recent works

By Tai Hoi Ying

To See: Vision v.s. Observation

“To be or not to be”, this famous opening phrase from Act III of Shakespeare’s Hamlet brings reality into question.

Picasso painted the portrait of Gertrude Stein in his studio in 1906. At the 90th session, Picasso said: “I can no longer see you when I look at you,” and covered up the whole face he had painted. After his summer vacation, Picasso came back to his studio and finished the portrait in absence of the model, this time feeling satisfied. Picasso thus completed his well-known portrait of Gertrude Stein through a vision without gaze.1

Giacometti did not follow Picasso’s way.2 He insisted on looking at the object in front of him. His hands and eyes coordinated through time. As his brush strokes went on minute by minute, the traces of his movements were recorded on the surface of the canvas. The canvas documented the process of figuration, as well as the real traces of the passing of time. Giacometti insisted on continuing the search initiated by Cézanne rather than following Surrealism, which was à la mode at that time. Again he took up the search for reality by painting an apple on a kitchen table. Facing a simple object in a real space from a defined perspective, he persisted in the act of observation and painting until he was satisfied with the image produced.

Reality of Nature: Endurance v.s. Impulse

Cézanne’s investigation began with the problem of time. “A minute of the world goes by; it must be painted in its reality!” “I bring together all the scattered elements with the same energy and the same faith. Everything we see falls apart, vanishes. Nature is always the same, but nothing about her that we see endures. Our art must convey a glimmer of her endurance with her elements, the appearance of all her changes. It must give us the sense of her eternity.” For Cézanne, “nature exists more in depth than on the surface”, thus grasping it required “long labor, meditation, study, suffering, joy…” For one of his landscapes, he worked under pine trees for two months, capturing every element and every color tone day by day, until he gradually reached natural harmony. To Cézanne, art is not inferior to Nature. “Art is a harmony parallel to Nature.” In 1904, Cézanne concluded that “one must first of all study geometric forms: the cone, thecube, the sphere. When one knows how to render these things in their form and their planes, one ought to know how to paint.”3 Cézanne died in 1905. His life long effort “to experience eternity” became the guiding principle of Twentieth Century art.

Van Gogh, although in the same epoch as Cézanne, had a very different personality, and lived a short life (1853-1890). Quick, passionate, hard-working and anxious, he was only fully engaged in painting for a decade. Yet he had also set the standard for Twentieth Century art. Van Gogh and Cézanne reached the same goal through different ways.

Beyond Appearance: Imitation, Mechanical Reproduction, and Reality

This contrast can be seen throughout the history of art. The 14th Century Italian painter Cennino Cennini finished his monumental Il libro dell’arte (The Book of Art) in 1396 (some say 1437). As the third generation of the Giotto school, Cennino Cennini saw longterm apprenticeship as vital for developing the agile hands and imagination required for imitating nature and creating artworks. By the 18th Century French painter Chardin still inherited the tradition of patient apprenticeship. Once he met the philosopher and art critic Diderot (Salon of 1765), and Chardin asked Diderot to be lenient in his art criticism, because many painters have endured long and arduous experiences to get through their apprenticeship. But Diderot did not tolerate a mere mediocre “imitation of Nature”. He raised the stake of art to capture the “reality of Nature”.

By the 19th Century, with the Industrial Revolution, the mediocre way of imitation became even less appropriate. In 1835, the painter Daguerre realized his dream of “painting with light” by producing the first photograph. Photography was officially born in 1839.4 Gradually, the technology of quickly capturing and reproducing images of reality became popularized. Today, photography has become an inseparable part of our daily lives. Yet modern life never stops questioning “reality”. In the age of photography, Cézanne, Van Gogh, Matisse, Picasso, Giacometti, Balthus and other artists still searched for the “reality of Nature” through painting. Matisse saw the world again with the simplicity of children’s eyes. Giacometti, facing the same model, saw it differently everyday.

Reality: From Nature to Human

At this age when digital photography dominates the imagery of our times, let’s turn to Claire’s paintings: 15 canvases with Hong Kong’s banyan trees as subjects, 12 with Hong Kong’s cityscape as subject of composition. First, let’s look at the trees. They spread tall and wide, roots old and weathered, bizarrely twisting and winding. I can’t help to ask, how would a young woman like Claire have the insight to depict such things? Immediately coming to mind is one of Van Gogh’s paintings, Jeune Fille en blanc dans unbois, 1882. It is a composition of three trees in a row, branches and roots as the foreground; in the middle ground, a girl in white stands next to the second tree, holding and leaning from the tree with one hand; the tree in the foreground is so far forward that it makes the girl look small and far away, in sight but unattainable, giving off a sense of sadness. The girl and the roots are like oil and water; how can they coexist in the boundless forest? In the West they would see this as melancholy, a human condition since immemorial times. Another one of Van Gogh’s paintings, from his latest period, is Troncs d’arbres avec pré fleuri, 1890: the foreground also consists of thick trunks, painted with rough, contorted, quick brushstrokes. On the ground are plants, extending to a middle ground of a grass field with blossoming flowers; the further the distance, the greater the harmony, achieving a kind of peacefulness at the far end of the painting. Is it an expression of Van Gogh’s nostalgia? The beautiful bed of flowers in light yellow and green, with lines of black, blue and red, from crude to fine, weave a rhythm full of energy, creating a pure feast for the eyes. But right at the front are the wrinkled old trunks, among blooming flowers near and far. To me, the expanse of the earth evokes a diaspora’s nostalgia for his far away homeland. Van Gogh uses the old trunk to contrast the landscape, revealing the melancholy and nostalgia in the world, precisely representing the “reality” that we are discussing.

Claire’s Paintings: The Life of Nature

In Claire’s Banyan series, it is obvious that her intention is not to depict different types of banyan trees. If we look at Roots III, a fence stretches across sideways, intentionally cutting off the forest, leaving a single old banyan’s roots, limitedly spreading onto the earth’s surface. We focus on the roots, on the ground where light and dark create patterns — it is thus that life quietly unfurls. Contrasting with the warm tones in the highlights on the trunk are the grayish green tones of the roots, rendering them sombre, not at all glorifying. But this is precisely the true reflection of the strength of life! Let’s then look at Bursting Out, in which the attention is also drawn on old roots, but here, the light and dark contrast is no longer important — jumping out are red bricks and white stones that surround the tree; yet the strength of the tree is still the subject: roots curling and twisting, struggling with the brick. In the painting, the roots and stones are equally outlined by black strokes, emphasizing the severe and cold constraining power of the red bricks and white stones; meanwhile the artist puts hope in the dark green roots and grass, to be the life and strength among the flaming red — to break through is to succeed! Looking at the rest of the root paintings in the series, Interweaving, Taking Hold, Étendu... up until Enfolding, the viewer can impulsively connect to Beethoven’s Symphony, reaching the passion of “The Choral”!

Cityscapes and the Search for Reality

Let’s proceed to the Hong Kong landscapes. Starting with When the Sky is Clear, then Shatin I — on the moist, lush slopes wooden shacks and old houses compliment the hill. In Shatin II, old houses in the valley of Shatin are juxtaposed against the new towering housing estates. In Fotan Panorama (Shing Mun River), high-rises stand in great numbers on the river banks. In Old and New (Central), we don’t see the tourist symbol Victoria Peak, nor the financial and commercial powers’ hallmark skyscrapers, the world renowned brands in bustling malls, or the lofty street full of luxury cars.... The intention of the artists is clearly not to entertain the tourists’ hunt for novelty; her gaze is on the real scenes from the real lives of Hong Kong, the unadorned lives of the local people. In today’s world of globalization, consumer society, globalized economy and globalized lifestyles, nobody anywhere seeks to be different or alternative. However, while the landscape in the paintings are modest, we can still demand Diderot’s 18th Century attitude: not tolerating a conventional or habitual “imitation of Nature”.

Let’s look at the last painting of the series. Looking up at the verdant and lush hills we see a large row of concrete buildings, towering in the sky, yet containing an ineffable isolation and desolation. This makes one want to turn again to the bustling lives of Shatin, Kwai Chung and Fotan. Looking from high to low, from isolation to commotion, the artist is probably seeking the “reality of nature”.

I have been observing Claire’s drawings and paintings since she was a toddler. Every time I saw her in Paris, I always had new works to see. Even after she moved to Hong Kong with her parents, she came back to Paris years later and showed me a figure painting that had such sensitive and acute expressiveness that I still remember it clearly to this day. Eventually Claire went to the US to study art, and came to Paris once again as part of her curriculum, and so I was able to see her paintings during her study abroad period. At the beginning of this year, I received photos of her latest works. This time I couldn’t help myself but write about my thoughts upon seeing the paintings. I didn’t shy away from the fact that I’m an amateur writer, nor did I care that I would make a fool of myself in front of experts.

Spring 2014

1 Gertrude Stein, Autobiographie, 1934; Picasso, 1938.

2 James Lord, Un portrait de Giacometti, 1965 ; Giacometti biographie, 1983.

3 Conversations avec Cézanne, 1978, Macula.

4 Le daguerréotype français. Un objet photographique, Paris: Musée d’Orsay, 2003.

(Edited and translated from Chinese)

-----

Tai Hoi Ying is a renouned Chinese painter who has been living and working in Paris since 1970. His has been exhibiting widely for 40 years in museums and galleries in France, Switzerland, Denmark, Belgium, Taiwan, Macau, Hong Kong, U.S.A. etc.

“To be or not to be”, this famous opening phrase from Act III of Shakespeare’s Hamlet brings reality into question.

Picasso painted the portrait of Gertrude Stein in his studio in 1906. At the 90th session, Picasso said: “I can no longer see you when I look at you,” and covered up the whole face he had painted. After his summer vacation, Picasso came back to his studio and finished the portrait in absence of the model, this time feeling satisfied. Picasso thus completed his well-known portrait of Gertrude Stein through a vision without gaze.1

Giacometti did not follow Picasso’s way.2 He insisted on looking at the object in front of him. His hands and eyes coordinated through time. As his brush strokes went on minute by minute, the traces of his movements were recorded on the surface of the canvas. The canvas documented the process of figuration, as well as the real traces of the passing of time. Giacometti insisted on continuing the search initiated by Cézanne rather than following Surrealism, which was à la mode at that time. Again he took up the search for reality by painting an apple on a kitchen table. Facing a simple object in a real space from a defined perspective, he persisted in the act of observation and painting until he was satisfied with the image produced.

Reality of Nature: Endurance v.s. Impulse

Cézanne’s investigation began with the problem of time. “A minute of the world goes by; it must be painted in its reality!” “I bring together all the scattered elements with the same energy and the same faith. Everything we see falls apart, vanishes. Nature is always the same, but nothing about her that we see endures. Our art must convey a glimmer of her endurance with her elements, the appearance of all her changes. It must give us the sense of her eternity.” For Cézanne, “nature exists more in depth than on the surface”, thus grasping it required “long labor, meditation, study, suffering, joy…” For one of his landscapes, he worked under pine trees for two months, capturing every element and every color tone day by day, until he gradually reached natural harmony. To Cézanne, art is not inferior to Nature. “Art is a harmony parallel to Nature.” In 1904, Cézanne concluded that “one must first of all study geometric forms: the cone, thecube, the sphere. When one knows how to render these things in their form and their planes, one ought to know how to paint.”3 Cézanne died in 1905. His life long effort “to experience eternity” became the guiding principle of Twentieth Century art.

Van Gogh, although in the same epoch as Cézanne, had a very different personality, and lived a short life (1853-1890). Quick, passionate, hard-working and anxious, he was only fully engaged in painting for a decade. Yet he had also set the standard for Twentieth Century art. Van Gogh and Cézanne reached the same goal through different ways.

Beyond Appearance: Imitation, Mechanical Reproduction, and Reality

This contrast can be seen throughout the history of art. The 14th Century Italian painter Cennino Cennini finished his monumental Il libro dell’arte (The Book of Art) in 1396 (some say 1437). As the third generation of the Giotto school, Cennino Cennini saw longterm apprenticeship as vital for developing the agile hands and imagination required for imitating nature and creating artworks. By the 18th Century French painter Chardin still inherited the tradition of patient apprenticeship. Once he met the philosopher and art critic Diderot (Salon of 1765), and Chardin asked Diderot to be lenient in his art criticism, because many painters have endured long and arduous experiences to get through their apprenticeship. But Diderot did not tolerate a mere mediocre “imitation of Nature”. He raised the stake of art to capture the “reality of Nature”.

By the 19th Century, with the Industrial Revolution, the mediocre way of imitation became even less appropriate. In 1835, the painter Daguerre realized his dream of “painting with light” by producing the first photograph. Photography was officially born in 1839.4 Gradually, the technology of quickly capturing and reproducing images of reality became popularized. Today, photography has become an inseparable part of our daily lives. Yet modern life never stops questioning “reality”. In the age of photography, Cézanne, Van Gogh, Matisse, Picasso, Giacometti, Balthus and other artists still searched for the “reality of Nature” through painting. Matisse saw the world again with the simplicity of children’s eyes. Giacometti, facing the same model, saw it differently everyday.

Reality: From Nature to Human

At this age when digital photography dominates the imagery of our times, let’s turn to Claire’s paintings: 15 canvases with Hong Kong’s banyan trees as subjects, 12 with Hong Kong’s cityscape as subject of composition. First, let’s look at the trees. They spread tall and wide, roots old and weathered, bizarrely twisting and winding. I can’t help to ask, how would a young woman like Claire have the insight to depict such things? Immediately coming to mind is one of Van Gogh’s paintings, Jeune Fille en blanc dans unbois, 1882. It is a composition of three trees in a row, branches and roots as the foreground; in the middle ground, a girl in white stands next to the second tree, holding and leaning from the tree with one hand; the tree in the foreground is so far forward that it makes the girl look small and far away, in sight but unattainable, giving off a sense of sadness. The girl and the roots are like oil and water; how can they coexist in the boundless forest? In the West they would see this as melancholy, a human condition since immemorial times. Another one of Van Gogh’s paintings, from his latest period, is Troncs d’arbres avec pré fleuri, 1890: the foreground also consists of thick trunks, painted with rough, contorted, quick brushstrokes. On the ground are plants, extending to a middle ground of a grass field with blossoming flowers; the further the distance, the greater the harmony, achieving a kind of peacefulness at the far end of the painting. Is it an expression of Van Gogh’s nostalgia? The beautiful bed of flowers in light yellow and green, with lines of black, blue and red, from crude to fine, weave a rhythm full of energy, creating a pure feast for the eyes. But right at the front are the wrinkled old trunks, among blooming flowers near and far. To me, the expanse of the earth evokes a diaspora’s nostalgia for his far away homeland. Van Gogh uses the old trunk to contrast the landscape, revealing the melancholy and nostalgia in the world, precisely representing the “reality” that we are discussing.

Claire’s Paintings: The Life of Nature

In Claire’s Banyan series, it is obvious that her intention is not to depict different types of banyan trees. If we look at Roots III, a fence stretches across sideways, intentionally cutting off the forest, leaving a single old banyan’s roots, limitedly spreading onto the earth’s surface. We focus on the roots, on the ground where light and dark create patterns — it is thus that life quietly unfurls. Contrasting with the warm tones in the highlights on the trunk are the grayish green tones of the roots, rendering them sombre, not at all glorifying. But this is precisely the true reflection of the strength of life! Let’s then look at Bursting Out, in which the attention is also drawn on old roots, but here, the light and dark contrast is no longer important — jumping out are red bricks and white stones that surround the tree; yet the strength of the tree is still the subject: roots curling and twisting, struggling with the brick. In the painting, the roots and stones are equally outlined by black strokes, emphasizing the severe and cold constraining power of the red bricks and white stones; meanwhile the artist puts hope in the dark green roots and grass, to be the life and strength among the flaming red — to break through is to succeed! Looking at the rest of the root paintings in the series, Interweaving, Taking Hold, Étendu... up until Enfolding, the viewer can impulsively connect to Beethoven’s Symphony, reaching the passion of “The Choral”!

Cityscapes and the Search for Reality

Let’s proceed to the Hong Kong landscapes. Starting with When the Sky is Clear, then Shatin I — on the moist, lush slopes wooden shacks and old houses compliment the hill. In Shatin II, old houses in the valley of Shatin are juxtaposed against the new towering housing estates. In Fotan Panorama (Shing Mun River), high-rises stand in great numbers on the river banks. In Old and New (Central), we don’t see the tourist symbol Victoria Peak, nor the financial and commercial powers’ hallmark skyscrapers, the world renowned brands in bustling malls, or the lofty street full of luxury cars.... The intention of the artists is clearly not to entertain the tourists’ hunt for novelty; her gaze is on the real scenes from the real lives of Hong Kong, the unadorned lives of the local people. In today’s world of globalization, consumer society, globalized economy and globalized lifestyles, nobody anywhere seeks to be different or alternative. However, while the landscape in the paintings are modest, we can still demand Diderot’s 18th Century attitude: not tolerating a conventional or habitual “imitation of Nature”.

Let’s look at the last painting of the series. Looking up at the verdant and lush hills we see a large row of concrete buildings, towering in the sky, yet containing an ineffable isolation and desolation. This makes one want to turn again to the bustling lives of Shatin, Kwai Chung and Fotan. Looking from high to low, from isolation to commotion, the artist is probably seeking the “reality of nature”.

I have been observing Claire’s drawings and paintings since she was a toddler. Every time I saw her in Paris, I always had new works to see. Even after she moved to Hong Kong with her parents, she came back to Paris years later and showed me a figure painting that had such sensitive and acute expressiveness that I still remember it clearly to this day. Eventually Claire went to the US to study art, and came to Paris once again as part of her curriculum, and so I was able to see her paintings during her study abroad period. At the beginning of this year, I received photos of her latest works. This time I couldn’t help myself but write about my thoughts upon seeing the paintings. I didn’t shy away from the fact that I’m an amateur writer, nor did I care that I would make a fool of myself in front of experts.

Spring 2014

1 Gertrude Stein, Autobiographie, 1934; Picasso, 1938.

2 James Lord, Un portrait de Giacometti, 1965 ; Giacometti biographie, 1983.

3 Conversations avec Cézanne, 1978, Macula.

4 Le daguerréotype français. Un objet photographique, Paris: Musée d’Orsay, 2003.

(Edited and translated from Chinese)

-----

Tai Hoi Ying is a renouned Chinese painter who has been living and working in Paris since 1970. His has been exhibiting widely for 40 years in museums and galleries in France, Switzerland, Denmark, Belgium, Taiwan, Macau, Hong Kong, U.S.A. etc.